The following interview in my recent biography, “Beyond the Badge,” by author and journalist Rob Zaleski touched on a very painful experience with “anti-intellectualism;” one of the factors (along with violence, corruption, and discourtesy} that I believe is and has been arresting the development of policing in America. I specifically discuss this in my book on policing, “Arrested Development.”

The book was published in 2012, but I had some first-hand experience of this in 2017 when I was teaching a class on “community relations” to senior college students who were soon to graduate become police officers at the end of the semester.

When I was writing the book, I tried to find another word, but anti-intellectualism fit best. It is what has been keeping police back for far too many generations. Many police (and applicants) continue to eschew and disavow the benefits of higher education, research, experimentation, servant leadership, and systemic improvements.

Currently, many conservatives in our nation rail against, and even pass laws against teaching students about diversity and what is called “critical race theory.” This movement has even to the point of banning books that identify our nation’s shameful history of race discrimination and violence much of which has been captured in “The 1619 Project.”

This incident, however, turned out to be a good lesson. It’s not just that police pursue university degrees – it’s also important to examine how police are being taught and by whom when we decide our police need an advanced education.

Here’s chapter eighteen from Rob Zaleski’s book: The UW-Platteville Debacle.”

______________________

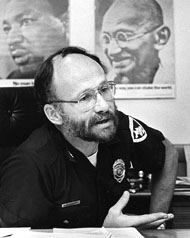

“In 2017, at age 78 , David Couper jumped at the opportunity to make another significant contribution to the evolution of policing in the Black Lives Matter era: He taught a course in policing, aimed at students pursuing a career in law enforcement, at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. He was excited to pass on the knowledge he’d absorbed in his more than three decades in policing – from walking a beat in a tough neighborhood in Minneapolis to running a department with 300-plus employees.

“It did not end well. He knew that Platteville, tucked in the southwest corner of the state in Grant County, is a conservative farming community of about 12,000 people, over 90 percent of whom are white. He was aware that Donald Trump had carried the county – though barely (51.3 percent) – in 2016. Nonetheless, he was shocked when 17 of the 29 juniors and seniors in a class he was teaching not only rejected many of his progressive ideas but signed a petition demanding that he be removed from his position.

“When the administration failed to fully support him, he abruptly resigned. When I brought up that distressing episode on an autumn morning two years later, Couper laughed and said he’d long ago accepted what had transpired and turned his focus to more rewarding things in his life. But the longer we talked, the more clear it became that he was still aggrieved, disillusioned and deeply disappointed in how his brief teaching career had ended. And still struggling to understand how we’ve reached a point where people refuse to even discuss contentious subjects.”

______________________________________

ZALESKI: I hate to conclude these interviews on a sour note, but I know how dismayed you remain over the sudden ending to your teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville in 2018, where for three years you taught a course for Criminal Justice students called Police-Community Relations.

You quit shortly after 17 of the 29 students in your class signed a petition basically saying you were unfit to teach the course – never mind that you were a police officer in Minnesota for six years and then police chief in Madison for another 21.

COUPER: Yeah, isn’t that something?

ZALESKI: When I brought this up earlier, you still seemed bitter.

Couper: (Laughs.) Let’s just say I’m still processing what happened, and I get less upset as time goes on. But it’s not too unlike the petition that my officers signed in 1973 in the Madison police department. That was extremely hurtful, too.

And that probably changed me more than anything else because it caused me to really question the police culture. I mean, I certainly had a track record that any cop would say, “Yeah, well, he’s one of us.” And yet here were these nincompoops who wanted to throw me out of town because I happened to have some different ideas about policing. And, naively, I thought maybe we could sit down and talk about these things so we could come to understand one another. But no, they wanted blood.

I think the one difference between 1973 and the situation I encountered at UW-Platteville was that in 1973 they were going to have to beat me with a stick to get me out of Madison. I wasn’t quitting. But in 2018, Sabine (my late wife and retired state police captain) could see I was really upset. And she said, “You know, you don’t have to do this. I mean, you’ve made your mark in your police career. If they don’t want you at Platteville, just quit. And if the department head wants to monitor your class for the rest of the semester, I’d just give her your notes and say, ‘Thank you and goodbye.’” And that’s what I did.

ZALESKI: But I assume you were shocked when you learned about the petition?

COUPER: You mean, did I have any hint it was coming? No. Because when I was first hired as a lecturer there, I taught an intro course to policing for freshmen, and their minds were pretty open. There was no pushback. But when I started teaching juniors and seniors, then the resistance started.

ZALESKI: I’ve read the petition. Among the charges were that your views were “incredibly one-sided, out of touch with the world in which we live and have no practical use in the ever-evolving world of policing.” It challenged your views on the use of deadly force, chastised you for being anti-gun and anti-law enforcement and said you “constantly asserted your opinions in lecture material.” Being in your class, the petition maintained, left a “foul taste” in the students’ mouths.

You’ve mentioned that Dr. Staci Strobl, the department head, also was upset that you’d criticized the students in your blog, “Improving Police,” and that she’d decided to monitor your classes for the remainder of the semester. She also informed you that your teaching contract wouldn’t be renewed. How did you respond to the criticism?

COUPER: Well, I remember her saying that people were offended by the blog. If I did criticize the students – and I don’t remember to what extent that happened – it was probably indirectly, and I think I took it down.

But I told her that I put a lot of things on my blog, and what about my rights to free speech? So it was OK for the students to do this, and I couldn’t respond in any forum?

(Strobl now teaches at Shenandoah University in Winchester, Virginia. Asked if she wanted to comment about the students’ petition and the decision not to renew Couper’s teaching contract, she said in an email that she didn’t feel comfortable commenting on employment issues, for legal reasons. “I can say,” she wrote, “that from a personal point of view, Couper brought a very important social justice orientation to police studies at UW-Platteville.”)

ZALESKI: You have a liberal-activist background, and Platteville is a conservative farming community. Seems like a textbook example of where we’re at in this country.

COUPER: Absolutely. It’s white fragility. In Robin DiAngelo’s book (White Fragility, published in 2018), she explains it exactly the way it is. So does Noble Wray, who’s been teaching “Unconscious Bias” at the New York Police Department. (Wray, who is Black, was Madison’s police chief from 2004 to 2014.)

He said that in every class there are guys sitting in the back of the class, and their attitude is, “You ain’t teaching me shit, buddy.” And then you start talking to them and it’s like, “Well, don’t you start telling me about racism.” They’re so upset that somehow they have any responsibility in this system of racism in our country that they’re shocked by it and outraged.

ZALESKI: So, in the class you taught, was there a rejection of this idea of systemic racism in police departments?

COUPER: Well, we didn’t even get that far. We were just doing the history, talking about what (author) James Baldwin would have to say, what currently Ta-Nehisi Coates would have to say, taking a look at why people of color say this about our society and what is your responsibility as a police officer.

I told the students, “You might be working in some all-white community in northern Wisconsin, but guess what? A whole bunch of people from Chicago who don’t have the same skin color as you might be vacationing up there or driving through, and you’re going to run into Black people at some point and you’re not going to be able to avoid it.

“And statistics show there seems to be a tension between how people of color view police, so you’ve always got to be prepared for a tense situation and you’ve got to know the territory.” But they don’t want to know the territory. They don’t want to know that in any encounter they’re going to have with a person of color there’s going to be tension.

And it’s really — it’s my theory, anyway — it’s the responsibility of the police to diminish that somehow. By being casual, by telling that person of color, “Look, you might’ve had a bad contact with a cop, but it ain’t me. I want you to know I’m going to be fair, we’ll talk about this afterward, so … let’s work together on this problem.”

ZALESKI: I can appreciate what you’re saying. Our family vacations in northwestern Wisconsin every summer, and we don’t like our son-in-law – who’s from Sierra Leone – driving to the country store by himself. It’s Trump country, which can be pretty scary for a Black person.

COUPER: Oh, absolutely. And what would a lot of white people say about that? “Oh, c’mon, you’re just making that stuff up.”

ZALESKI: I’m guessing the hardest thing for you to swallow regarding that petition was the suggestion that – after spending most of your adult life in policing, including 21 years as Madison’s police chief – you were somehow unfit to teach that class. That’s rather audacious, I’d say.

COUPER: (Laughs.) Well, yeah. And I wanted to get my day of justice. I wanted to meet with those kids and have them defend the position they were taking. I wanted to tell them, “What you’ve done here would not even pass the basic rudimentary standards of writing a police report. You’ve used ad hominem attacks, you don’t have any basis for this.” I thought it would be a great teaching experience. But I was prevented from doing that, and that upset me – this notion that I couldn’t fight back (against their claims).

And that’s a big change in the academic system from what I experienced, where professors were pretty much hallowed people and you listened to what they had to say. And you could reject it or not, but you certainly didn’t try to attack them. At least in my academic days.

ZALESKI: Again, a perfect example of where we are in this country regarding racial issues.

COUPER: Oh, absolutely. These kids – the majority of them – were about to take jobs as a police officer in some town or city. They were weeks away from putting on a badge and a gun. They refused to take the time to consider that my attitudes are about policing are not that far-fetched.

Now, some faculty members with police backgrounds would probably not accord themselves with my philosophy of policing, nor would I endorse theirs. But isn’t that what academia is all about? I mean, let’s be fair about this.

ZALESKI: Who was the administrator who said you couldn’t participate in the discussion with students to defend yourself?

COUPER: Well, that came down from the academic dean, Dr. Melissa Gormley, and she was in Europe, so nothing could happen until she came back from Europe. And I said I really couldn’t continue to teach that class with this sort of elephant in the room.

ZALESKI: Did any students come to your defense?

COUPER: I got one email of support, from a male student. Who essentially said, “I don’t know what happened, I wasn’t part of this and I want you to know that I appreciate your ideas.”

ZALESKI: How sad that you had to experience that at this point in your life. I’m sure it was tough to accept.

COUPER: Well, the good thing is it helps me to work on practicing what I preach about forgiveness. It’s a process and I’m getting better at this, but, you know, it was really hard not to say I will not forget that uncivil behavior on the part of people who claim to be fair and compassionate…

______________________

I have to weigh-in here in defense of David and what he was trying to accomplish in his class. I had students come to me complaining about him, he was presenting a VERY different point of view on policing and this viewpoint is incongruent with what they teach in the academy, it’s much deeper. Yet for someone who seeks to enter the craft of policing (it’s not a profession) the ideas he presents were too overwhelming for those who have a hard enough time just learning and following correct procedures.

I’m fond to putting it this way, the police are not in the social justice business. They are in the criminal justices business and these are two very different concepts. The “wisest” police officers have an understanding of social justice issues but it takes education and years of experience to reach this point.

Our police organizations also do not support it, in fact, the oath of office does not support social justice activism. But that does not mean that individual police officers, through the use of their enormous discretion, should not consider the big picture when making decisions about what might be “the best possible outcome” in a given situation.

Anti-Intellectualism simply means “lack of wisdom.” We like to think that wisdom is gained through a liberal arts education but not always, life experience in my view, is the very best teacher. Unfortunately, these days, students come to the university not seeking an education, just a degree. David’s teaching was just to much for them them to absorb.

LikeLike

Here’s some interesting grist for the mill, Dave.

https://wapo.st/450gahu ________________________________

LikeLike

Much agreed — the future and salvation of policing a free society will, I believe, be in precisely that — more women in the ranks and for more departments to sign on to “The 30×30 Initiative.” See https://30x30initiative.org

LikeLike

Check out the “30×30 Initiative.” It’s a way out of the present dilemma that our police face today — https://30x30initiative.org

LikeLike

It is a start but I will still be very wary of hiring them due to the fact that our police training is still inadequate and they can be just as vicious against honest cops plus maintaining the blue wall of silence. You wonder how many policewomen right now are hard-core conservatives who don’t care about the Bill of Rights and the US Constitution? There are too many women who seem to lost their feminine side and are now acting on the bad sides of males that they are always complaining about. In addition, you are hearing more and more stories about women playing politics against each other in the workplace and many women have stated that they don’t want to work with other women. All this talk of sisterhood has gone out the door considering the fact that Covid 19 has really brought out the worst in people in only two years. If police politics are bad right now, I can’t imagine how it will be when you get a good number of bad female police officers occupying many police leadership positions

The Afro-American female police who was head of the Portland police wasn’t any help to her community when it was revealed that Portland police were assisting right-wing protestors in storing food, radio gear, and even weapons at their protests. She was also very combative in her remarks regarding antifascist counter-demonstrators.

LikeLike