[Note: Time marches on. As a mid-way octogenarian, I wanted to share my life with others so that what I learned (and failed at) could be helpful to the next generation of young men and women who have decided to serve their communities as police officers. As a teaser, I have reprinted Rob Zaleski’s preface to my biography. May it be helpful…]

DAVID COUPER: Beyond the Badge; Reflections of an Ex-cop

To Dave Zweifel, former editor of The Capital Times, who believed in me.

“What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others.” — Nelson Mandela

PREFACE

Long before the fatal shootings of Trayvon Martin (2012) and Michael Brown (2014) by white police officers ignited the Black Lives Matter movement, I’d contemplated writing a book about David Couper.

Though it’s been nearly three decades since Couper stepped down after 21 years as the reformist – and highly controversial — police chief in Madison, Wisconsin, to enter the ministry, I knew he was still writing a daily blog and impassioned op-ed pieces and appearing on radio talk shows; in other words, still stirring the pot on social issues, especially those pertaining to policing.

I’d first interviewed Couper on a hot, steamy day in August 1990, eighteen years after he’d been hired as police chief, for a profile I was doing for The Capital Times, Madison’s afternoon daily, where I’d worked since 1981. He allowed me to spend the day with him, and it struck me even then how unconventional he was – that he came at life from a sharply different angle and actually had a blueprint for what he’d hoped to accomplish as chief. I found him to be cordial, egghead smart, very much in charge, but also cautious.

He would pause before answering probing questions, and sometimes respond tersely, with just one or two words. And, as other reporters had discovered over the years, he was very protective of his personal life.

That was understandable, of course. From the moment he’d accepted the job, he’d been under attack not only from conservative politicians but from the rank and file in his department, particularly those in the police union. They were not thrilled that the Police and Fire Commission had chosen a “lefty peacenik’’ to run the department. They’d been battling Vietnam War protestors from the University of Wisconsin since the mid-1960s and weren’t about to sit idly by and allow this cocksure, unabashedly liberal police chief to alter the city’s rigid law-and-order approach to demonstrations and other disturbances.

For Couper, the low point of the almost daily conflicts occurred when both local dailies published a letter from Richard Daley, the president of the police union, lambasting Couper after one of his teenage daughters, who was struggling with alcohol problems, was arrested for drunk behavior in downtown Madison. If Couper couldn’t control his own family, Daley maintained, how could he possibly run a department with 300 employees?

I left that 1990 interview impressed and intrigued. I wanted to know more about this complex, outspoken rebel in blue who, upon his surprising retirement just three years later, had dramatically transformed the police department by hiring a large number of women and people of color, and establishing himself as one of the most progressive chiefs in U.S. history.

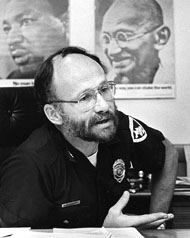

I’d also been taken aback. Prior to the interview, I’d assumed Couper was perturbed about his widely-publicized image as Madison’s hippie-pinko police chief. But it became clear from the moment I settled into a chair in his nondescript, window-less office in the City-County Building that he not only wasn’t upset by the image, he relished it and even promoted it. How else could one explain the prominently displayed posters of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. on the wall behind his desk?

Clearly, he wanted it known that he was the antithesis of the traditional, hard-boiled chiefs who still led police departments throughout the country – and who, in Couper’s view, were stuck in the dark ages.

I had little contact with Couper after that interview, though I continued to admire him from afar – he was making headlines, it seemed, almost weekly – and was as shocked as everyone else when he called a press conference in 1992 and announced he’d be stepping down to become an Episcopal priest. Nothing in his resume or previous interviews had even hinted that was a possibility.

Then, in 2011, almost two decades later, he contacted me out of the blue and asked if I’d be interested in a temporary free-lance job helping edit a book he was writing that he hoped would raise the alarm about the militarization of police, a frightening development he believed was largely due to the country’s overreaction to 9/11. Having lost my job at The Capital Times in 2008, I gladly accepted. And while we met only a few times over the next several months, it was during those sessions that I began to fully appreciate what an extraordinary life he’d led – a life filled with an abundance of emotional highs and noteworthy achievements, countered by a series of wrenching personal setbacks that had tested his faith to the utmost. (His self-published book, Arrested Development, came out in 2012.)

I was also fascinated by his never-ending desire to make the world a better place – and by the fact that he actually had compelling ideas that might, in a small way, accomplish just that. This is a story that needs to be told, I remember thinking.

At the time, I was working on my own book, on progressive Wisconsin activist Ed Garvey (Ed Garvey: Unvarnished). But shortly after University of Wisconsin Press published it in 2019, I drove out to the old, charming farmhouse near Blue Mound State Park, about 40 minutes west of Madison, that Couper and his wife Sabine had bought in the summer of 1980 and proposed that we collaborate on a book about his life. A book with a similar Q&A format as my book on Garvey, which would enable Couper to expound not only on his insightful, timely – and yes, provocative — views on policing, but would lift the veil on his private life as well. More specifically, a book that would explore how an under-achieving kid from a working-class upbringing in the Twin Cities, whose dad was an alcoholic and sold trucks for a living, and whose mother was cold and distant, a kid who’d cared mainly about sports and girls, could evolve into a fierce defender of human rights and one of the most influential law enforcement officials in the country.

(Sabine, who was president of her high school class, once asked Couper if he’d ever held any leadership positions during his school years. Zero, he responded with a chuckle – noting that he still remembered how crushed he was at not being chosen as a crossing guard in sixth or seventh grade.)

I also wanted to learn how the second chapter of his adult life had gone – the 22-year period where he’d first served as pastor of St. John the Baptist Episcopal Church in Portage, about a half-hour north of Madison, and then as part-time pastor at tiny St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in North Lake, a small town in ultra-conservative Waukesha County that had become a hotbed for Donald Trump’s hostile MAGA movement.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Couper was as enthused about the idea as I was. However, while he was proud of his achievements and truly believed he’d had an impact, he confessed that he’d done some incredibly foolish things in his life, had made many mistakes and probably had as many critics as fans. But that was OK, Couper said. At this advanced stage in his life, he welcomed a book that would give an honest, accurate assessment of David Couper, warts and all. But he questioned whether it would have much readership value.

Though he turned 83 shortly after our final interview, his mind was still razor-sharp, and he retained the vitality of someone half his age. At six-feet-two and a lean 220 pounds, with a gold earring in his left ear, he looked much as he did when I first interviewed him three decades earlier — largely, he suggested, because he still practiced judo, taekwondo and aikido (a Japanese martial art that involves swords); and still lifted weights several days a week at a fitness center in nearby Mount Horeb. The only give-away to his octogenarian status was the craggy lines in his weathered features.

Our first interview took place on a crisp, gray morning on December 11, 2019, in an old frame house at the edge of Couper’s heavily forested property – roughly 100 yards from David and Sabine’s farmhouse — where Sabine’s parents had once lived. (Both are deceased.) And I sensed immediately that this venture would, at the very least, be gratifying — not just because Couper was so forthright and still harbored strong opinions on a wide array of subjects, but because he was refreshingly unpredictable.

(While he ranked Barack Obama and Jimmy Carter – that’s right, Jimmy Carter – as the best U.S. presidents of the past half-century, he considered Bill Clinton one of the worst. “He was just such a little namby-pamby, mama’s boy,” Couper moaned of the country’s 39th president. “He stood there on national TV and said he didn’t have sex with ‘that woman.’ Well, Bill, what do you call sex? What exactly do you mean? And that pretty much turned me off to his whole presidency.”)

We had 18 more interviews over the next year, four of them on Zoom because of the Covid-19 epidemic; those interviews, I must admit, exposed the comedic ineptitude of two aging technophobes trying to cope with poor Wi-Fi- reception due to the hilly terrain. On two occasions in the dead of winter, Couper had to climb into his red pickup truck and drive to the top of a nearby ridge so that we could regain contact. But he never despaired, never grumbled, never lost his enthusiasm for the project.

Our last several sessions, once the pandemic (temporarily) slowed, the snow disappeared and shirt-sleeve weather arrived, occurred in the cozy, screened-in cabana beside their in-ground swimming pool, over glasses of V-8 tomato juice, with Couper in the same frame of mind that he’d been from the beginning: calm, reasoned, upbeat, always contemplative, always itching to challenge any stereotypes that the public had formed about him. And always open to opposing points of view. Which, I suspect, is a big reason so many people revere him.

After we’d completed our final session in late November 2020 – which, frankly, was a sad day for both of us — I was confident that the interviews had succeeded in capturing the real David Couper and that it was, indeed, a story worth telling. I also felt privileged that this astute, compassionate, complicated man was willing to share the details of his remarkable life with me.

I think many who feel they know Couper will be surprised – perhaps even shocked — by some of his revelations. But I’m guessing they’ll also recognize the man who not only is dismayed by the bigotry, sexism and hatefulness he’s witnessed – especially in the last decade – but the man who made it clear decades ago that his mission in life was to explore ways to help people engage and respect one another.

At 83, it was still his mission. What better legacy than that?

_________________________

If interested, Zaleski’s book can be purchased from Little Creek Press.

My book on improving our nation’s police, “Arrested Development: A Veteran Police Chief Sounds Off About Protest, Racism, Corruption and the Seven Steps Necessary to Improve Our Nation’s Police,” is also available. You can find it on Amazon with this introduction:

“Can police be improved? Couper thinks so. This is about the 20-year transformation he led in the city police department in Madison, Wisc., the history and subculture of policing, and then the seven steps police are going to have to take to improve today. In Madison, Couper successfully brought educated women and minorities into a basically all-white, all-male police department. He and his officers handled hundreds of protests using the ‘Madison Method’ of crowd control. Within the department he developed a collaborative leaderships style called ‘Quality Leadership.’ Since his retirement, he has been concerned about the increasing militarization of our nation’s police and their slow progress forward – an ‘arrested development.’ This is his third book on policing.”