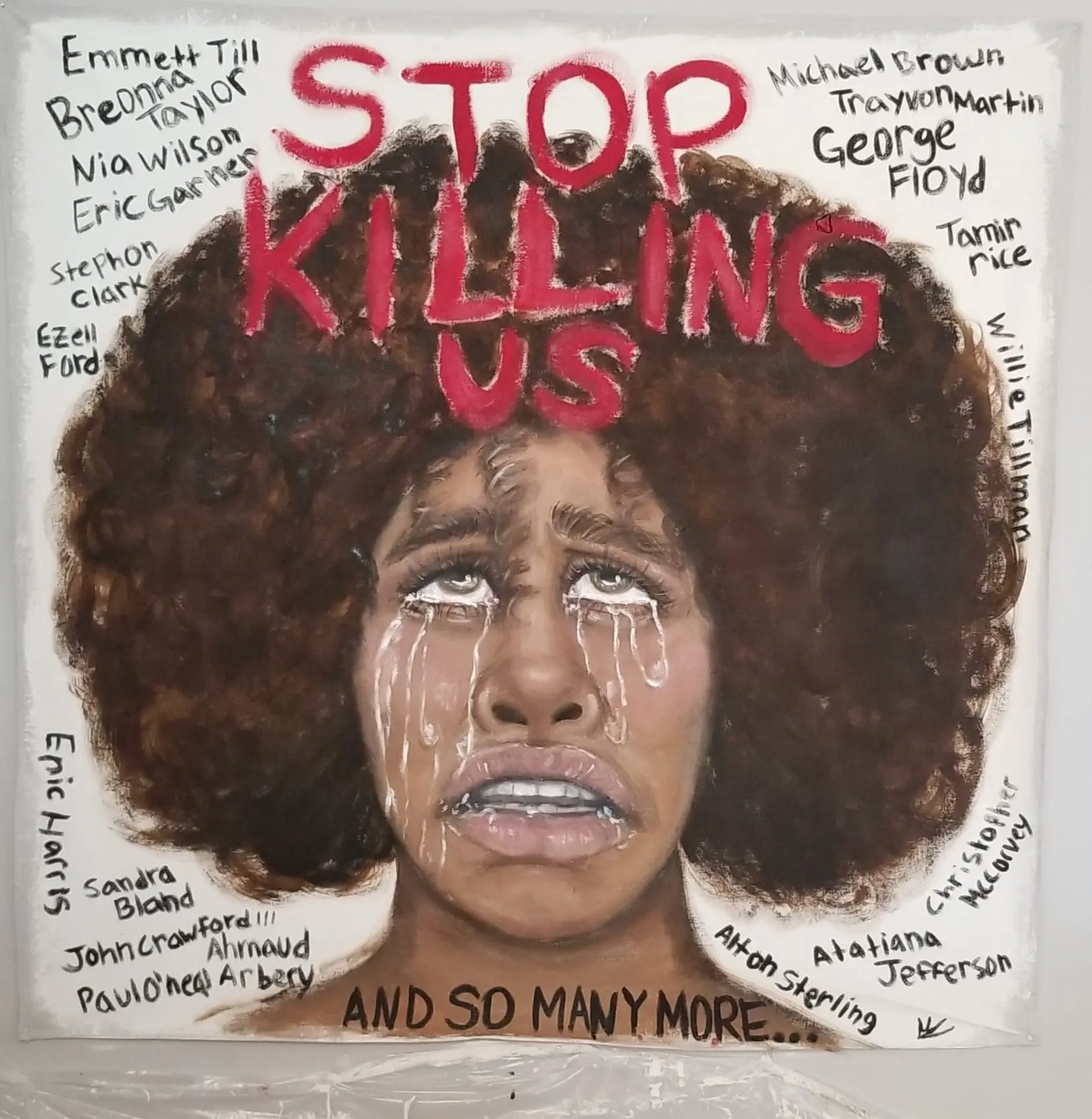

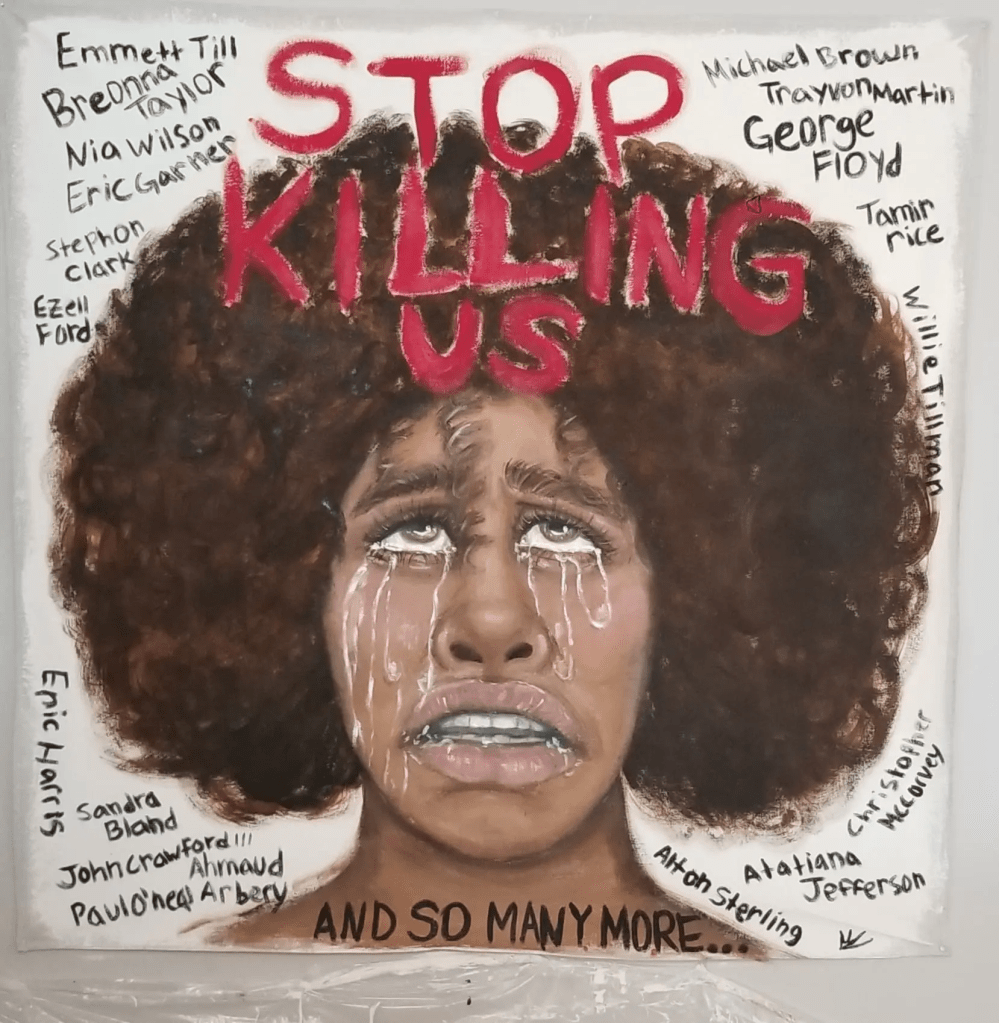

In 2014, Michael Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, MO. Six years later, and after much analysis, debate, and disagreement George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis, MN. A decade has separated the two national incidents. Between these two events, many others have died by police action in questionable situations.

During and after my 33 year career and into retirement, I have watched, analyzed, and continued to think about my life’s mission — improving police. What I have seen as responses to questionable uses of police deadly force, fall into two categories — 1) Send “bad cops” to jail and/or 2) Take away some of the duties of police which involve persons mentally and emotionally unstable and assign them to mental health workers.

In my opinion, neither of these strategies will do what I believe most of us want in America — that is, to have police actually “protect and serve” all citizens and are intelligent, emotionally stable, well-trained, connected to the community, and led by mature leaders committed to constantly improving the work of policing a democracy.

Let me put it this way: You cannot improve a system by punishing those who are failing in their work. But you can improve a system by analyzing their work, asking those who do the work how to do it better, and soliciting feedback from those who are impacted by the work police do. Into this mixture are also needed leaders who are great cops and committed to seeing the values and mission of policing a free and diverse society such as ours actually carried out.

Interestingly, I ran across a news article from almost ten years ago that, I believe, captures the question before us — “How can the number of citizens killed by police each year be reduced?” Given the numbers, and the death rate compared with other democratic nations, we are out of the ball park, top of the list. (Our rate of citizens killed by police is 33.5/10M, Canada is 9.8, Germany is 1.3, England 0.5, and Iceland and Norway is zero.)

It is also important to highlight here the work of the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) in their guidelines on use of force and the ICAT system of force control. From the guidelines: Guiding Principle #1: The sanctity of human life should be at the heart of everything an agency does. Agency mission statements, policies, and training curricula should emphasize the sanctity of all human life—the general public, police officers, and criminal suspects—and the importance of treating all persons with dignity and respect.“

In 2015, Chuck Wexler, the Executive Director of the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), of which I was one of the earliest members, took a number of police chiefs to Scotland to see how their police (unarmed) handled threats by guns and knives. Some learning came out. One police chief from a very large east coast city, remarked after seeing how police in Scotland were trained to often disengage, “Take a step back and talk to people, because it works. Your style is exactly the way I want my officers to be.”

But, of course wanting something and making it happen are two distinct steps in exemplary leadership.

Another member, who was a police chief in a large southern city said this:,“We in American policing are missing the boat in the respect for human life, altogether. The notion drilled into new officers, ‘better to be judged by 12 than carried by six’ — is misguided.

But he went on to take a deeper venture into what happens when a human being takes the life of another. Most citizens have seen the agony and anger from those who have had a family member killed by police — from the victim’s perspective. Police leaders deeply know of that pain in meeting with the family of a person killed by a police officer.

But there is another deep, and often silent, tragedy behind police shootings — the impact it has on those who have had to take another person’s life — even if it was absolutely necessary. He went on, “I’ve watched great cops get into a shooting that destroyed their lives. They may have been exonerated, but they knew their careers were over, they became alcoholics, they lost their marriages, because they couldn’t handle that they took somebody’s life, even if it was a good shooting.”

Having to take a life doesn’t just negatively affect family and community members — it affects the lives of those we train and call to protect us. Even the most heroic shooting can inflict a severe moral injury and the career of an officer. Think about it!

Now one would think that this would be a wake-up call; that police would come to see that taking a life can be dangerous to those who must do it in the line of duty. However this is not often discussed. Why would it not be?

I suggest It is because the present subculture in American policing; a subculture that emphasizes peer loyalty even when the peer is wrong. It is a subculture that resists peer intervention even when the peer officer is about to do something that may get him or her fired or put in jail. It is a subculture that promotes a “them versus us” attitude when approaching or working with community members. It is a subculture that believes as the chief mentioned, “it is better to be judged by twelve than carried by six” (indicating better to have to go to court than be carried to your grave. It is a subculture that does not embrace the ethic that all life is sacred.

Yes, there are positive aspects of the subculture in terms of support, teamwork, and collaboration, but the negative aspects of this subculture tend neutralize the importance of respect, trust-building and working with community members in maintaining a safe and peaceful communities. A good example of the power of this subculture was voiced by a top command officer during the Scotland experience. This commander supervised one of the largest police training functions in our nation. “If I go back and I do say, ‘Back up,’ ” (referring to one of Scotland’s primary tools to contain violence), “they’re going to say, ‘What happened to you?’”

Subculture matters. It has to do with attitude and how police are selected, trained, rewarded, and led once they go into the field.

Being able to lead an improvement in the police subculture, especially with regard to the sanctity of life (all lives) is absolutely necessary for the future of American policing — and is not going to be easy.

____________

You can read the full article from 2015 below. What still needs to be done? Digest this blog and read my book about how one city did it — and it took a decade. So, you’d better begin now! Press on!