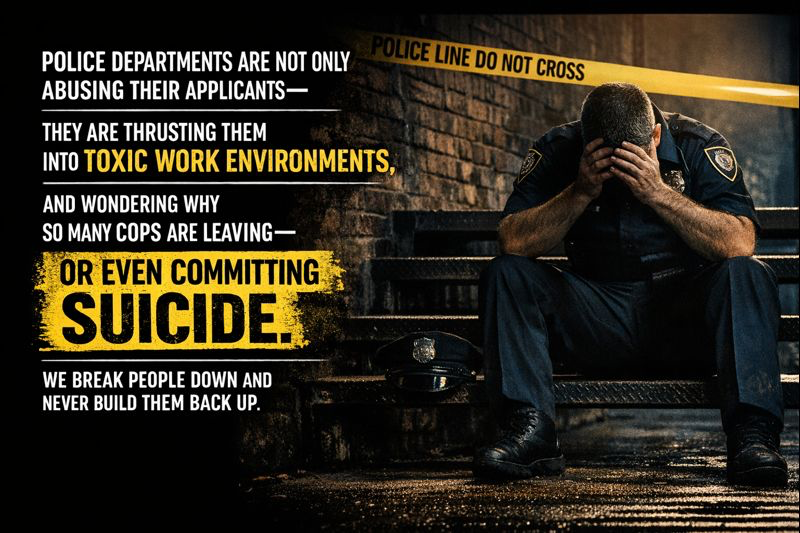

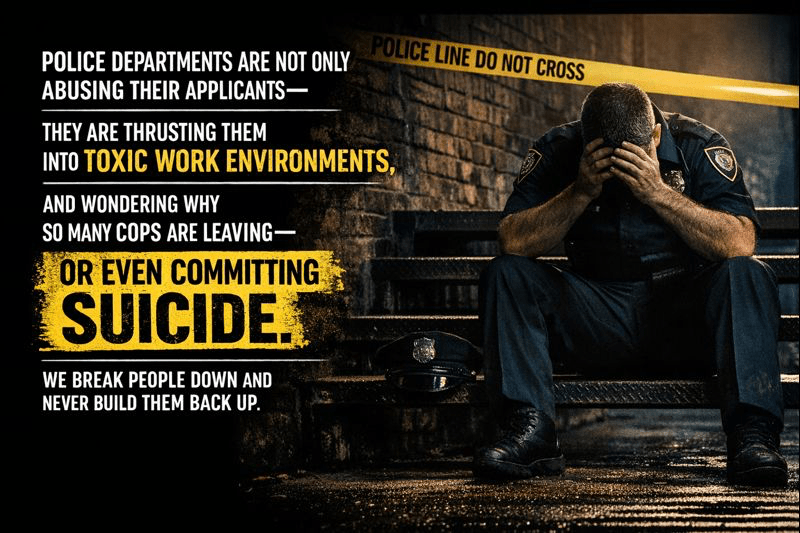

The Toxicity Doesn’t End at Graduation

Even if police academies reformed tomorrow, the police employment crisis would persist—because the problem does not stop at recruit training. It continues inside the station house, reinforced daily by leadership practices that belong to another century.

Too many police leaders simply do not know how to lead people.

They know how to issue orders.

They know how to enforce rules.

They know how to protect their own authority.

What they do not know—what they were never taught—is how to develop human beings.

Across the country, younger officers describe the same environment: rigid top-down command structures, public humiliation disguised as “accountability,” indifference to wellness, and supervisors who neither listen nor learn. Innovation is treated as insubordination. Questions are labeled “attitude problems.” Officers are told to “pay their dues” in workplaces that quietly erode morale, ethics, and commitment.

This is not leadership. It is institutionalized insecurity.

Research in organizational psychology is unequivocal: workplaces dominated by authoritarian, fear-based management suffer higher burnout, lower performance, increased misconduct, and faster attrition. Encouragement, coaching, psychological safety, and participatory leadership—especially for younger professionals—produce better judgment, stronger ethical behavior, and longer careers. Policing ignores this evidence at its own peril.

The result is predictable. We recruit young people with the promise of meaningful service, then subject them to academies that confuse abuse with discipline—only to send them into station houses where outdated leaders repeat the same toxic patterns. And then we act surprised when they leave.

Let’s say this plainly: you cannot build a modern police profession on 20th-century command-and-control leadership.

If police agencies want to solve the recruiting and retention crisis, they must confront an uncomfortable truth. The problem is not “this generation.” The problem is how we train, supervise, and treat them—from day one in the academy to their final day in uniform.

Until policing abandons hazing as training and authoritarianism as leadership, it will continue to hemorrhage exactly the kind of thoughtful, ethical, service-oriented people it claims to want. And there will continue to be a lack of interest among young people today to serve in such an organization.